This post was written by Grosvenor Teacher Fellow Jennie Warmouth.

My Grosvenor Teacher Fellow expedition to the Arctic was in June of 2019, at the tail end of the school year. I had the challenge of returning to school that September and making meaning of this expedition for my next cohort of students. I showed them an image from the expedition of a gloved hand holding garbage and said, “I went looking for microplastics in the Arctic but ended up finding large macroplastic all over the shoreline. Why and how did that happen?”

All of my second-graders resonated with the ice cream scoop in the image and thought it looked like the sporks we used for meals at school. They hypothesized that one of our sporks ended up in the Arctic. The “mystery” of how human-made plastics could be found in the High Arctic provided a catalyst for everyone in the school to learn more about ocean currents and how plastics move. It was completely student-centered: they hooked into that tiny image because it matched with something they know well. Most of my students receive free breakfast and lunch; their cutlery was packaged in a plastic sack and they handled it twice every day, so it was a concrete part of their lives.

From there they started having mixed feelings about this tool they were using daily. They learned about the impact of plastics on the Arctic animals and we used the Geo-Inquiry Process to ask questions such as, “Why do we use these sporks?” “How much do they cost?” We calculated that the school disposed of 72,000 sporks per year. My students started reflecting that sometimes they don’t even open the spork, but it still goes in the trash can. That hadn’t registered with any of them before and invited some self-reflection.

My students put together a PowerPoint summary of their findings and concerns to present to school administrators. I taught them to anticipate the perspective of the decision-makers. We asked, “What might their counterpoints be?” (such as costs) and “How can we prepare and present alternatives?” The kids practiced their presentation in class and then presented it to their principal and representatives from the school district. The administrators agreed that they were willing to make a change and transition the use of single-use plastics to reusable metal silverware, but they were concerned students would throw away the metal silverware because they were used to throwing away the plastics. Financially that wouldn’t be sound and would contribute to more pollution. So their caveat was that my students had to find a way to guarantee that the metal silverware wasn’t thrown away.

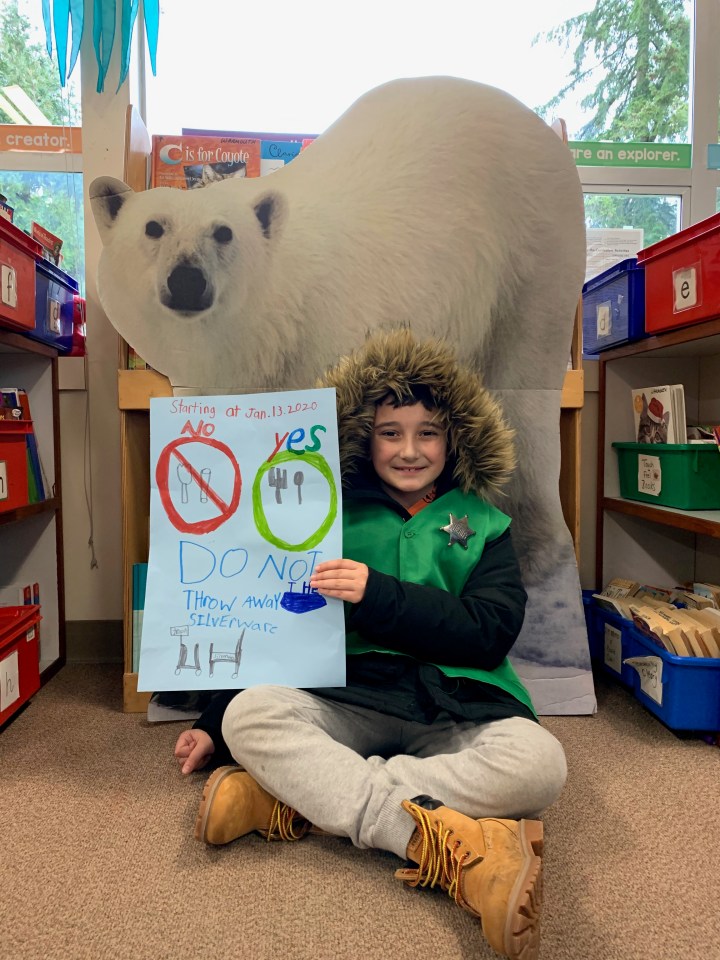

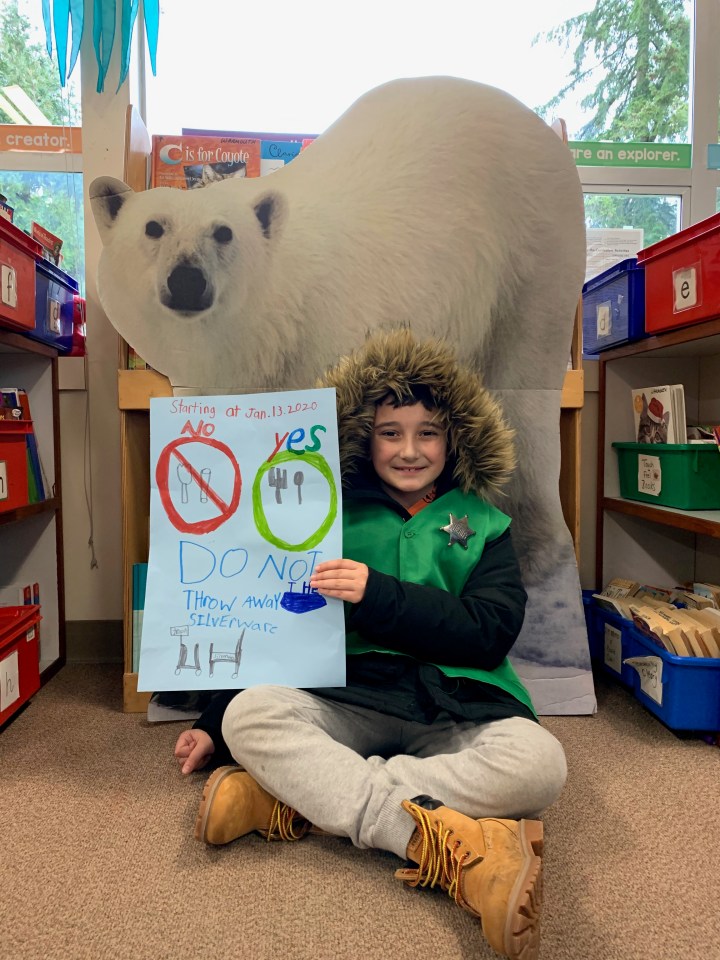

In response, we built a committee of Silverware Patrol officers to educate their fellow students and monitor the garbage cans. I invested in making it fun and exciting — I bought green vests, sheriff badges, and telescopic magnetic wands (in case anyone accidentally threw away a piece of silverware). We accepted applications from all the kids in the school to join the squad. Kids had to write an essay describing why they wanted to join and what their environmental concerns were. We received 70 applications and my second-graders evaluated them based on a rubric. It was so wonderful and authentic; they were reading other kids’ writing and perspectives in the position of a teacher with a focus on content, mechanics, etc. Ultimately, I accepted every application to participate, but it was really affirming for my second-graders to be in that position of leadership.

We created training sessions to teach the Silverware Patrol to communicate with others, how to use the tools, how to handle their uniforms, etc. There were times when silverware went into the trash, but it was mostly located and pulled out. It also created an opportunity for conversation — kids telling other kids why not to throw away the silverware was more powerful than that decree coming down from a teacher.

Our Ar(c)t(ic) Art Project competition was born out of the depth of these conversations and the work and research my students did around the Silverware Patrol. While curating images for our messaging to the leadership, we started digging into the analysis of visual images and talking about the power of that gloved hand and why it resonated. My students were tasked with finding other images they thought were compelling and talking about why they leveraged an emotional response. This inspired us to create an art project inviting other kids to engage in that line of thinking and design something related to High Arctic conservation. My students designed assessment rubrics based on principles of design blended with some of their own rules (they are adamant about no penguins in the art because penguins only live in Antarctica!). I involved some National Geographic Explorers and local artists to serve as a panel to give us feedback on actual principles of design, and the contest is now open and accepting submissions.

I believe that when kids understand and care about the impact of their own choices and behaviors on others, they begin to make changes. I believe they’ll be the decision-makers of the future who have some important decisions to make around the health of their planet. In terms of learning theory and child development, they’re at a pivotal time when they’re with me and I’m helping create a lens for them in how they see the world. I take it to heart. I want them to make balanced and far-reaching decisions that are informed. Empathy, compassion, and agency are important, and I want them to know how to stand up for themselves and how to advocate for what they need as individuals.

Empathy for the earth helps develop my students’ universal focus that we all are part of this place together — we are interconnected with animals, each other, and our environment. It opens up an opportunity for conversation around conservation, and sacrifice has been a big theme with the Silverware Patrol. It is harder work to do the Silverware Patrol job; it’s easier to use the single-use plastic, but making that change was worth it. It’s really impactful for them to do that work and put in the time, have the conversations, and register that this is a choice. It’s a little bit of a sacrifice but it’s worth it even though they can’t physically see the impact of the spork not being in the trash. Had the project just been teacher-focused, had I just picked up the phone and called the principal to pitch the idea, it wouldn’t have had the same meaning.

Interested in sharing the Ar(c)t(ic) Art Project with your students? Click here to learn more — submissions are due December 21! And learn more about the Silverware Patrol and how to take action in your community here.