Sign up for the Smarter Faster newsletter

A weekly newsletter featuring the biggest ideas from the smartest people

In 2022, scientists found microplastics — pieces of plastic less than five millimeters long — in human blood. Since then, they’ve been discovered throughout the human body, including in our lungs, kidneys, livers, hearts, and brains.

So, why do we have all this plastic in us, what does it mean for our health, and what can we do about it?

Living in a plastic world

Plastics are a wonder material. They’re tough, lightweight, flexible, sterile, and cheap, which has made them hugely popular — since the 1950s, production levels for plastic have increased faster than for any other material. We’re now producing 440 million tons of plastic every year, with the total still trending upward.

Unfortunately, there’s a major tradeoff for all the benefits of plastic. Not only is the production of it bad for the environment, contributing to global warming, but so is the way we treat the material after we’re done using it: only about 9% of the world’s plastic waste is recycled, while 19% is incinerated. The rest goes into landfills (50%) or becomes litter (22%).

Researchers have known since the 1960s that plastic waste was an issue, but the problem took a new shape in 2004 when marine biologist Richard Thompson published a paper in the journal Science in which his team reported the discovery of microscopic plastic fragments and fibers in the ocean environment.

They dubbed these pollutants “microplastics.”

“The fragments appear to have resulted from degradation of larger items,” the researchers wrote. “Plastics of this size are ingested by marine organisms, but the environmental consequences of this contamination are still unknown.”

In 2024, Thompson led a new study, also published in Science. This time, his team looked back at the 7,000 microplastics studies that followed their 2004 discovery to see what we now know about the pollutants — and the answer wasn’t great.

In 2004, @ProfRThompson led the first ever study – published in @ScienceMagazine – to use the term #microplastics to describe the tiny plastic particles being found in the marine environment. pic.twitter.com/izRUXzgoNn

— University of Plymouth (@PlymUni) September 20, 2024

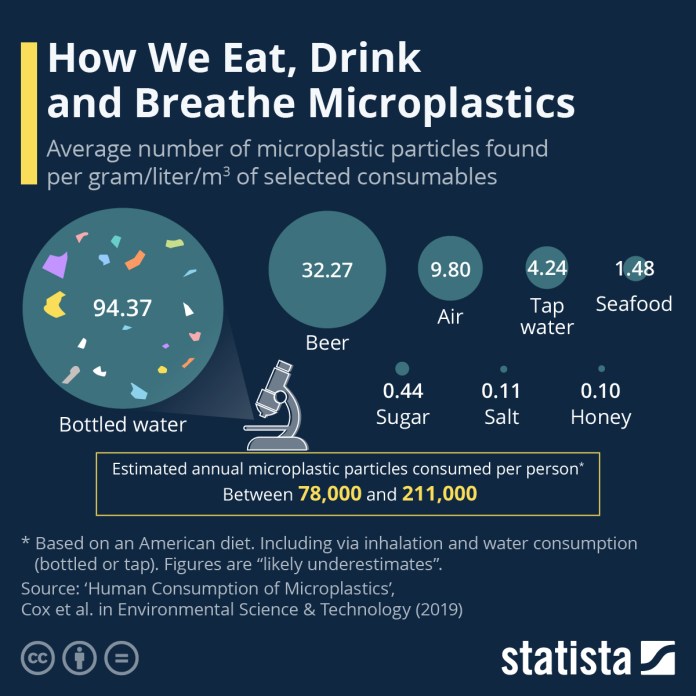

Not only had the amount of microplastics in the ocean increased over the past two decades, scientists had also found the particles in tons of other places — they’re in the air we breathe, the water we drink, and the animals we eat, as well as hundreds of species outside our food chain. They’ve also been found in other foods that we consume, from vegetables to ice cream.

As for where all these microplastics were coming from, Thompson’s team was right that many were once a part of larger pieces of plastic — polyester clothing and synthetic rubber tires proved to be particularly large sources of microplastics in the environment. The tiny plastic pellets which are used to create larger plastic products are a big contributor, too — at various points in the supply chain, they can slip into the environment.

Identifying microplastics and their sources was just the start, though. A major focus of research has been on determining the impact of these particles, and that’s led to more bad news.

“After 20 years of research, there is clear evidence of harmful effects from microplastic pollution on a global scale,” said Thompson in a press release about the new study. “That includes physical harm to wildlife, harm to societies and cultures, and a growing evidence base of harm to humans.”

Mitigating microplastics

That evidence has been enough to inspire officials in some places to take action to try to reduce the amount of microplastics in the environment.

In 2015, for example, Congress passed the Microbead-Free Waters Act, which banned the inclusion of plastic microbeads in toothpaste, face wash, and other products. Some states and cities have also banned some single-use plastics, which can break down into microplastics once discarded.

These policies aren’t enough to significantly reduce the amount of microplastics in the environment, though — the most straightforward way to make that happen would be for the textile industry and tire manufacturers to stop creating products with so much plastic.

“[W]e can not dramatically reduce microplastic pollution without leadership from the textile industry and tire manufacturers to produce consumer products that don’t add to the growing problem,” said Mark Gold, executive director of the California Ocean Protection Council.

These are massive, global industries, though, and convincing them to change en masse how they operate (or getting governments around the world to force them to change) won’t be easy, especially since we still don’t know for sure just how bad microplastics are for human health.

There’s no straightforward path to figuring it out, either.

“We know these microplastics are all over the place. We don’t know whether the presence in the body leads to a problem.”

Albert Rizzo

Because microplastics are everywhere, we can’t exactly compare the health of people who are exposed to them to people who aren’t to determine their possible effects, so our real world studies have no controls — already a big strike against them.

“Plastic” is also not just one thing. There are more than 13,000 different chemicals used in plastic production, which complicates matters even further — how do we know which ones are causing which health effects and therefore need to be regulated or banned? There isn’t any systematic testing of these chemicals in humans, much less the countless potential combinations of them that are used in plastic products.

Scientists can — and have — exposed human cell cultures to certain kinds of plastic chemicals and microplastics and recorded how often the cells experienced inflammation, DNA damage, or death. They’ve also performed controlled studies on animals and recorded their effects, noting how exposure to certain levels of microplastics can cause mice to experience organ failure, develop immune disorders, demonstrate signs of dementia, and more.

Even though these studies (and common sense) suggest that having microplastics in our bodies is probably harming us in some way, they don’t prove it, though.

“Are the plastics just simply there and inert or are they going to lead to an immune response by the body that will lead to scarring, fibrosis, or cancer?” Albert Rizzo, chief medical officer for the American Lung Association, told National Geographic in 2022. “We know these microplastics are all over the place. We don’t know whether the presence in the body leads to a problem.”

Looking ahead

Proving a link between microplastics and health issues may be a huge challenge, but as Thompson noted, the evidence base of harm to humans is growing.

A study published in March 2024, for example, analyzed plaques removed from the clogged heart arteries of about 300 people with heart problems and found microplastics in about 60% of the samples. People with microplastics were 4.5 times more likely to have a heart attack, stroke, or die within 34 months of the plaque removal surgery, compared to those without.

That correlation does not prove causation — it could be that people who are sicker for other reasons are also ingesting or retaining more microplastics, and that’s what the study is picking up on. But the result is certainly consistent with microplastics worsening health problems.

We don’t have to wait as researchers work to unravel the connection between microplastics and human health to start mitigating the problem, though.

“Nobody’s saying there’s no safe way to use plastics.”

Richard Thompson

We already know that plastic waste in the environment, big and small, is killing wildlife, degrading ecosystems, and generally just making the world a worse place, and tire wear particles, which include plastics as well as a range of other unpleasant substances, have long been known as a major source of pollution.

To combat this, some people are developing better plastic recycling tech and sustainable plastic alternatives. Others are collecting and recycling the plastic waste that’s already in the environment and taking steps to prevent new waste from reaching it.

These are still relatively small-scale solutions, but in 2022, the members of the United Nations committed to establishing a legally-binding agreement designed to end plastic pollution. This agreement is expected to include concrete plans for reducing plastic production, phasing out particularly problematic plastics, redesigning products that create significant microplastics, and more. A UN committee will meet in South Korea the week of November 25 to finalize a draft of the agreement.

“Nobody’s saying there’s no safe way to use plastics,” Thompson told Yale Environment 360. “It’s just that we need to start making them to be safer and more sustainable than we have done so far, and that’s what the treaty needs to help us do.”

This article was originally published by our sister site, Freethink.

Sign up for the Smarter Faster newsletter

A weekly newsletter featuring the biggest ideas from the smartest people